visual poetry

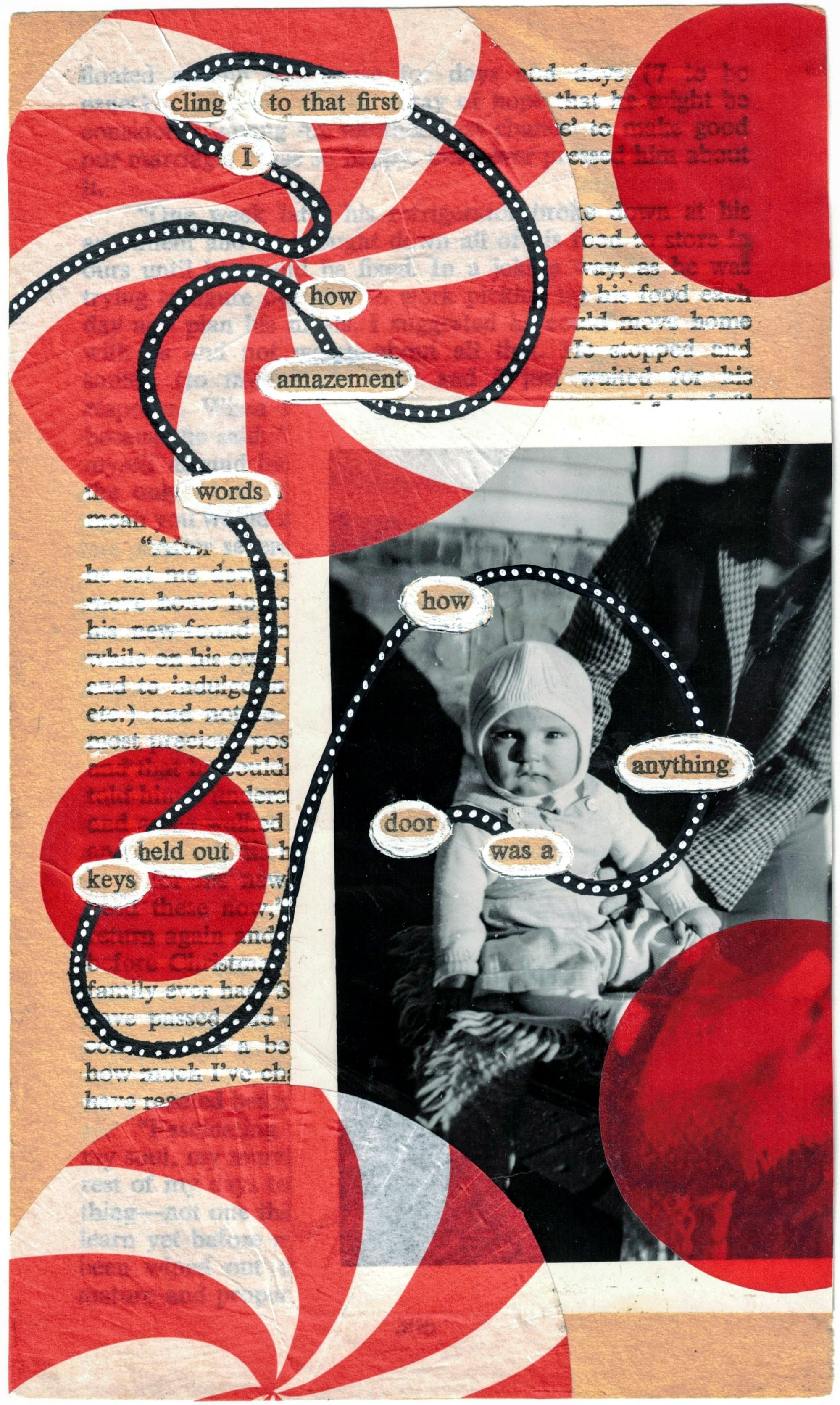

Below are pages from my book in progress — a collage/erasure transformation of Fascinating Womanhood by Helen Andelin, a best-selling “self improvement” book for wives published in 1963. Find links on my publications page to see more. Click images to enlarge.

-

Fascinating Womanhood was a bestselling “self-improvement” book for wives, published in 1963. It became the manual for the “femininity” movement of the 60s and 70s, promising women who felt alienated by second-wave feminism that all would be well if they would become “ideal women” – by suppressing their own capability, showering their husbands with flattery bordering on worship, and making themselves adorably girlish. It was written by Helen Andelin, whose religious background matched my own. My alteration of the book began in college, when I discovered it in the library where I attended religion classes. Repulsed by the book's gospel of self-limitation, I penciled a faint protest in the margins and returned it to the shelf. Then I went on to live my messy life, which was full of the tensions all women face.

Decades later, I found a yellowed copy of the book at a thrift shop, and bought it with the intent to burn it. But that would not be enough; for me, the book’s message – that my aspirations toward strength and self-possession were unnatural, selfish, and immoral – acted as a sort of personal kryptonite, exacerbating my own tendency toward paralyzing guilt and self-doubt. I knew I could not neutralize that power by destroying one random copy. But what if I could do battle with the content, confronting it page by page, word by word, and deliver poetry, art, and defiance from this text? Yes, but I was so disheartened by this book that for years, every attempt to undertake the project soon flickered out. Not until my child was grown, and not until the pandemic lockdown of 2020, did I find myself free enough to undertake it.

The act that allowed me to move forward was this: I cut off the spine on a bookmaker’s guillotine, and absolved myself from the obligation to take the pages in their original order. Even then, the book’s limited language gave me difficulty – how could I wrestle poetry from such an impoverished text? Soon, necessity forced me to invent new techniques, to free me from the order of the language, as well as the pages. I began to build words I needed, one letter at a time, and drew ligatures to carve a new path for the reader’s eye. The work has been painful: at every step, I have felt the fact that I am not the kind of woman my culture raised me to be. Yet, finding many women’s names in the source text, I imagined each of them as a protagonist in her own story, fighting for the same dignity I yearned for. When it was difficult to work for my own sake, I found I could work for them.

And I am nearing completion: the book lies before me, transformed, nearly in its entirety, into its own rebuttal. The work has also transformed me: bound by the straitjacket of this text, I am finding ways to move. Gagged by it, I am finding a way to speak.

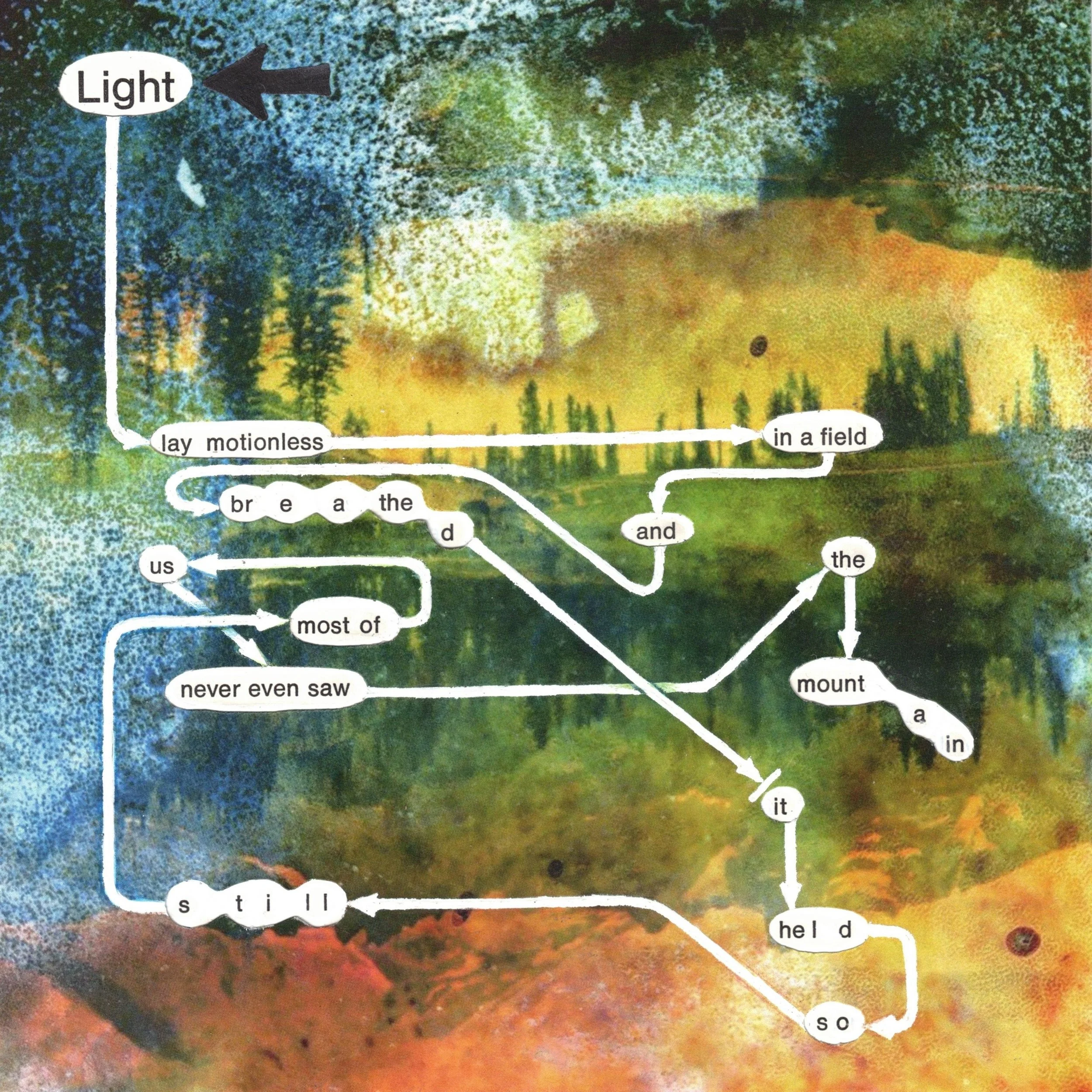

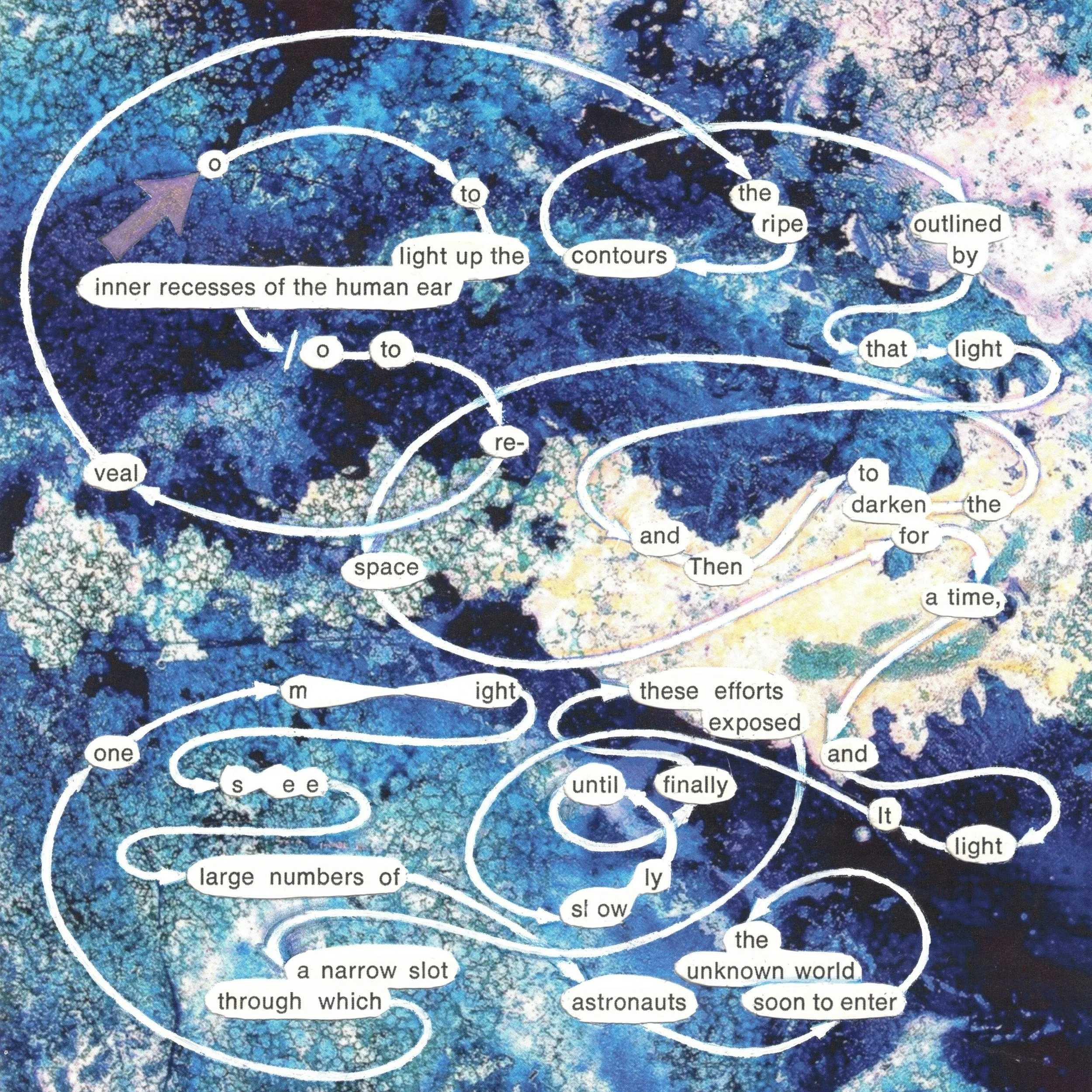

Below are visual poems from Beyond the Frame, an anthology of poetry inspired by the vintage photograph collection of Patty Paine. Medium: pages from Light and Film, from Life Library of Photography (Time-Life Books, 1970), overlaid with laser-printed images, altered with white ink, Prismacolor pencils and an Exact-O knife. The book is available from Diode Editions: Beyond the Frame

-

When my father’s Polaroid camera delivered pictures that “turned out badly,” I always secretly loved the spectral flare, the dreamlike distortion of color. In her Wrecked Archive, Patty Paine pushes the material strangeness of Polaroid film beyond recognizable images into that kaleidoscopic dreamworld glowing at the edges of so many pictures from my childhood. I responded to her partial undoing of the images by wrecking them further, then reconstituting them as visual poetry. While a Polaroid camera spits out a chemically active stack of layers that must be peeled apart, my work was to fuse half-disintegrated layers back together. I cut into laser prints of Paine’s Wrecked images with a knife and layered them over pages from Light and Film, a 1970 volume from Time Life Library of Photography, to reveal poetry I’d created by staring at the text until my mind had dissolved all unnecessary words. It is often said that photography stops time; in this anthology, poetry is an alchemical agent, returning the image to time, decay, and, while we have it, a bright window of meaning.